THE BOURBONS AND THE TWO SICILIES

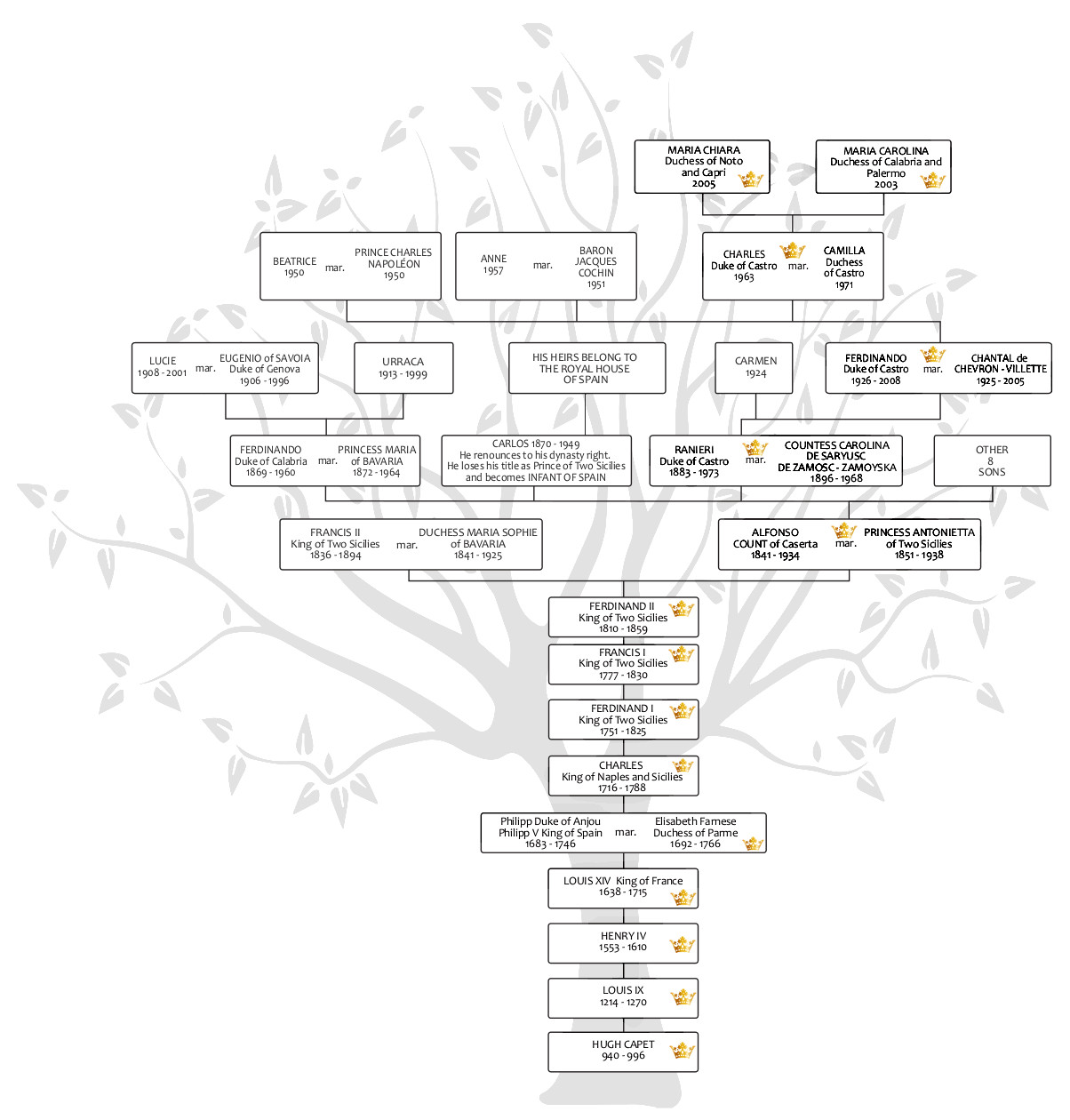

The Bourbon dynasty of the Two Sicilies originated from the Capetian dynasty. It traces its roots back to Hugh Capet, who became the King of France in 987. The Bourbons later rose to prominence with Henry IV, the first Bourbon king of France, and Louis XIV, his grandson, who expanded their influence. The Bourbon family eventually established a branch that ruled over the southern Italy regions, known as the Two Sicilies, alongside their reigns in France and Spain.

One of Europe’s oldest and most important dynasties thus reigned over Italy’s largest and most populous state before unification, during the delicate period of transition from the modern to the contemporary age, as the country took its first steps towards industrialisation, returning a sovereign to Naples after several centuries of foreign rule.

THE REIGN OF CHARLES

(1734-1759)

Charles of Bourbon, son of Philip V of Spain and Elizabeth Farnese, was initially intended to inherit the Duchy of Parma and Piacenza, from which his mother came, and the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, ruled by Gian Gastone de’ Medici who had no direct heirs.

The meeting in 1731 between the nineteen-year-old Bourbon prince and the elderly Grand Duke was instructive for the future king, who three years later was to lead the Franco-Spanish troops in battle, driving out the Austrian army to conquer the kingdoms of Naples and Sicily. From that time on, King Charles decided not to turn his back on his century, and to gather around his throne all the living forces of the two new kingdoms he was called to rule. The king began numerous public works, attempted to improve the transport system, founded the famous porcelain factory in Capodimonte, supported the first archaeological excavations in Pompeii and the construction of the San Carlo opera house of Naples.

He also commissioned Luigi Vanvitelli to build a lavish palace in Caserta, to compete with Versailles. Charles’ prudent approach to foreign policy, which helped him to stay on the throne during the War of the Austrian Succession and the Seven Years’ War, together with the policy of secularisation implemented in agreement with the other Bourbon monarchies, were a good example of enlightened absolutism and marked an era of undoubted progress for Southern Italy.

Charles reluctantly left Naples after his elder brother, Ferdinand VI of Spain, died with no successor. The king, having promulgated the Pragmatic Sanction of 1759 governing the hereditary relations between the kingdoms of Spain and Naples, was forced to leave for Madrid together with his queen and their first-born, also named Charles. Naples and Sicily were left to the third son Ferdinand, just eight years old.

THE LONG REIGN OF FERDINAND

(1759-1825)

The young King Ferdinand was entrusted to a regency council led by the minister Bernardo Tanucci. The reins of government remained in the hands of the Tuscan minister even when the king reached his majority in 1767 and the work of enlightened reformism continued. The Franco-Spanish influence was mitigated by the forging of ties with Vienna after Ferdinand was married to Marie Carolina of Habsburg-Lorraine, the daughter of the great Maria Teresa.

After the French Revolution, in 1799 the kingdom was invaded by the troops of republican France. The monarchs fled to Palermo under the protection of the British fleet, while a republic was proclaimed in Naples. The restoration of the monarchy just six months later was well-received by most people in southern Italy, led by Cardinal Fabrizio Ruffo of Calabria. However, there was a dangerous rupture with the local bourgeoisie, as evidenced in Vincenzo Cuoco’s Historical Essay on the Neapolitan Revolution of 1799.

The second Sicilian period (1806-1815), caused by another French invasion of Southern Italy, led to the island being given its own constitution in 1812, by Prince Regent Francis. The constitution was the first of its kind to be granted in Italy outside the Napoleonic system.

In 1815, Ferdinand was able to return to Naples definitively, accompanied by his minister Luigi de’ Medici, who the following year oversaw the merger of two states into one: the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. The decision provoked Sicilian resentment, while a number of young officers linked to the Carbonari fomented the rebellion of 1820. Ferdinand managed to resolve the situation thanks to the support of European powers, who gathered at the Congress of Laibach (Ljubljana) and decided to send the Austrian army to the South. Ferdinand died on 4 January 1825 at the age of 73, after a reign lasting more than sixty years.

THE REIGNS OF FRANCIS I AND FERDINAND II

(1825-1859)

During his short five-year reign, King Francis I continued his father’s policies, under the guidance of the minister Medici. In 1827, he obtained the withdrawal of the Austrian expeditionary forces still stationed in the kingdom. A lover of science and botany, Francis introduced new systems of cultivation, irrigation and breeding, by promoting agriculture, his great passion. Shortly before his death in 1829, he established the Royal Order of Francis I, a precursor of today’s civil orders of merit, which rewarded those who distinguished themselves in culture, science or public service.

Almost a century later, the realm once again had a twenty-year-old ruler, when Ferdinand II took the throne on 8 November 1830. At a time when England and France had begun their industrialisation, symbolised by the invention of the railway, King Francis was supporting the construction of

Italy’s first railway: the Naples-Portici line, built in 1839. This was followed by a series of firsts in many different fields, including the inauguration of the steelworks in Pietrarsa, the first steamship company in the Mediterranean and the Vesuvius Observatory. During the revolts of 1848, Ferdinand was the first king in Italy to grant a constitution. However, the experiment with Parliament was unsuccessful and within a few months the system had reverted to absolutism, while Sicilian independence was repressed. The king died in the Royal Palace in Caserta on 22 May 1859.

FRANCIS II AND NAPLES

AGAINST ITALY

The reign of Francis II began in the midst of a dangerous international crisis, following the Second Italian War of Independence. The end of Austria’s influence on the Italian peninsula, the rise of Cavourian Piedmont and British hostility all led to the Expedition of the Thousand in 1860, finally supported by an invasion of the Savoy army from the North.

Faced with such flagrant violation of his neutral kingdom, Francis II appealed to international law, at a time when the topic had been recognised for some time, but not yet well-defined, as would be the case after the World Wars. The king withdrew to the Gaeta fortress with his young queen Marie Sophie, defending his right to rule with honour, but in vain.

Francis died in 1894, exiled in Austrian Trentino, leaving no direct descendants and transferring his rights to his brother Alfonso, Count of Caserta (1841-1934).

After the Act of Cannes in 1900, the rights of succession passed to Alfonso’s son Ranieri, Duke of Castro (1883-1973) and then to the Duke’s descendants: his son Ferdinand (1926-2008) and grandson Carlo (1963), who is now committed to continuing the story and legacy of a kingdom and dynasty, combining tradition and innovation within a modern European monarchy. This is the context for Prince Charles’ historic decision in 2016 to disregard the Salic law and to refer instead to the European law prohibiting discrimination between men and women, by naming his first-born Princess Maria Carolina, Duchess of Calabria, as his legitimate heir.